Jack, Pete and I are all back in Florida for a week or so. Gas prices are low so Pete and I drove with Lemon and got in the day before Christmas eve. Jack was shredding the pow pow in Vail and flew in on Christmas eve.

This is the first time I have been home in 10 months, which come to think of it, might be the longest I have ever been away. Leading up to the trip back I was pretty excited about it.

Spending time with Pops and Sis is something I miss terribly. The two of them are an anomaly. Their relationship is like no other father-daughter relationship I have ever known, in the most positive of ways. They laugh and cuss and piss each other off and take care of each other and protect one another. They are perfect.

Winston has been in town as well and has been kicking it at the rompin room with us since we got back. We have had some interesting nights so far.

The night we got it we went to the Old Venice Pub on the Island where my old friend Dan Macmillan tends to the bar. Dan is a bit older than me, say 10 years, I think. He was the first person besides my father that liked Jazz and Kerouac. He also listened to the Minutemen. A well rounded cat. When I was very very young, like 8, he was friends with a guy named Rusty Rustemeyer, a friend of my parents who lived in the rompin room for a while before it was the rompin room. When we met again almost a decade later, it freaked him out. "I smoked weed with your dad while you played basketball," he said. "You were a little kid."

So we went to the OVP. We thought we might run into some people from high school but that it wouldn't be a bi deal. We would have a few beers and get our homecoming started on the right foot. 40 minutes later Winston was pissing at the bottom of the stairs because he couldn't stand to wait in line in that chamber of broken dreams. It was a fucking wake-up call. I saw everyone I never thought I would see again once I moved up North. With a few exceptions, most notably Josh Sinibaldi, who was ostensibly my very first friend in this world, who is getting married to long-time swetheart Megan Archer in a week or so, it was terrible. People have graduated from college, gotten strung out on drugs, gone to rehab, had kids, bought houses in North Port (the worst place in the world)and for the most part are miserable, working for their parents or crashing in their old bedrooms. It is true what the say: You can't come home again.

So the next night we decided to just go with it, to smother ourselves with the ugliness of our roots, an exercise in deprivation. We played ping-pong and watched racist rednecks bob their heads above their Budweiser to Kanye West and 36 Mafia. Strange, sad Irony haunts these parts and it makes is disparaging.

But then their was Christmas. We woke up and I made a pretty reat breakfast that consisted of Jack's favorite: Biscuits an Gravy with scrambled eggs. Then we opened the presents that each of us were able to scrape together with our respective finances. For the last few years we have all become a rather engaged family, always finding new periodicals and books to share with each other. Christmas is a giving and taking of knowledge and right now the tree is surrounded with books ranging from "Obamanomics" to several issues of seminal literary magazines such as The Antioch Review, Tin House and The Paris Review. If you walked into our ouse, you would think we were much more high-brow than we really are.

BShort came over a little later and we embarked upon a culinary journey of Biblical proportions. We made a turkey, stuffing, green bean casserole, sweet potato mash, mashed taters and gravy, cranberry sauce and croissants. I have never cooked a turkey. I assumed that it would be a disaster but fun. Strangley, after the bird was cut and everyone had taken their first bite, we all agreed that it may very well have been the most delicious turkey we have ever tasted. And everything else was great, too.

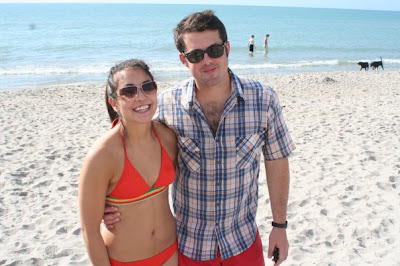

Then Elle came to town. At that point in my home stay, I was ready to lose it. Elle's arrival was something I was looking forward too very much, a coming up for air as it were. I drove up to Tampa the day after Christmas to shoot photos of her and Amanda for Cakeface. Sequins and Boleros and Steak and Shake was involved.

The next night Jesso drove up from MIA to meet up for a DIY performance at Amanda's High School dance teachers house, in her garage. It was really neat, seeing something like that in a very upper middle-class neighborhood. It was the equivalent of a early-90's basement hardcore show and everyone seemed to enjoy their piece.

Elle came home with me that night, back to the rompin room to see what my existence was comprised of for most of the 23 3/4 years I was alive before we met. We spent a day and two nights at home with the family. We took Lemon to the dog beach. We ate sushi and saw a movie. We went on a Florida date. She felt the whit talcum of Siesta Beach between her toes. We had a very nice time. Then she flew home. I drove her to the airport Monday morning and left for New York. This blog is public domain and is supposed to be representative of the person i try to present myself as to people. Serving that function, it leaves little room for vulnerable statements. But, casting that aside, I must say that I miss Elle. I will not go into detail but know that it is not pretty. She is going to Mexico on the 4th which means that we will not see each other for another 2 weeks. Not good.

To round out the experience, Kayla had her last operation to rid her of kidney stones yesterday at All Children's Hospital in St. Petersburg. I will one day write about my experience there, when Kayla was born, and almost died from a heart defect. I will write about the Ronald McDonald house and about why people who oppose Universal Healthcare should be forced to sit and watch these families suffer. I will also write about the strange bottomless feeling you get in your stomach walking around there, looking at the ground in the parking lot and seeing the remains of abandoned pacifiers and toys. It is strange and tragic and at times beautiful. That hospital is a testament to Science's beauty and to the utter improbability of a benevolent God existing. No benevolent creator would allow such gentle souls to suffer pointlessly. No God would allow such things to happen to children.

But Kayla is fine now. She had a really rough day but she is ok. We are watching Gilmore Girls. That's what I will be doing a for a while now.

Happy New Year everyone. Lets make it a good one.